- Jul 11, 2019

- 5 min read

A few weeks ago, I was in Cape Town catching up with a friend. My short visits back home tend to coincide with exam time for most South African universities, so seeing anyone my age is usually a rarity.

“I’m finally doing it,” he proudly announced. “I’m taking my leave of absence.”

The guy couldn’t have sounded more relieved. Truth be told, I had been expecting this announcement for some time after he had told me over a year ago he was on the verge of quitting his studies.

Here you might shake your head and think, “Well, there goes another one.” In South Africa, only 15% of university students make it from their first year all the way to graduation – and for most of them, it isn’t out of choice. Financial issues, lack of family support and desperation compound to force this decision on many. But for my friend, the decision was entirely voluntary. He started his first year at the University of Cape Town as an actuarial science student – that notorious killer of a degree that is said to break people’s souls while making others millionaires. Actuarial science is no joke and he knew from one look at his deplorable grades that he wasn’t going to keep his scholarship for long if he didn’t change degrees fast.

So that’s what he did. He changed degrees, as many people do. Now, two years into his information systems major, he has finally decided to throw in the towel and instead focus on a business he started during high school which involves producing and selling energy-efficient water-heating units as a replacement for geysers – the “hot nozzle”. Through a series of fortunate coincidences and meeting the right people, he has now been linked with suppliers and manufacturers in China and looks forward to going into full production in 2020.

So you see, you can’t blame my friend for quitting. In fact, quitting might be the smartest thing he can do for his business right now.

My friend’s story certainly isn’t over – in fact, it marks the beginning of many ups and downs to come – but his attitude to his journey is what I find most inspiring. It’s an attitude that says, “Hey, what I’m about to do might be a total flop – but I’m at least going to try”.

How comfortable are we with failure?

Failure is a topic we like to keep theoretical. For millennials, the term has become a buzzword. You hear about people “failing” at their first startup venture or “failing” to secure funding. LinkedIn profiles now boast incomplete education sections as evidence that the person is a risk taker and go-getter despite having no degree. My personal favourite belongs to Peter McCormack, host of my favourite crypto podcast What Bitcoin Did.

Drop out! That’s thrillingly blunt. But failure is always easier to talk about in hindsight. If failure is such a valuable life experience according to the experts, life coaches and startup junkies, then isn’t it something we should actively seek out, or at least admit to openly at the time?

"The failure I’m talking about is the outright, embarrassing, you-haven’t-got-a-hope kind of failure."

My own unconventional academic and professional journey looks nice on the surface, but let me tell you, it’s only half as fun as it looks because failure is something I expect to be embedded in along the way. Take, for example, my experience working for a biodesign and digital fabrication lab while living in Seoul, South Korea.

I applied to intern at Fab Lab Seoul wholeheartedly anticipating rejection. You see, there is a certain liberty that comes with knowing you haven’t got a chance. “I have zero knowledge in this area and can offer nothing more than my curiosity,” I wrote candidly on my application form.

During the unexpected interview that followed, I reiterated that although I was deeply fascinated by 3D printing and biodesign, I unfortunately could offer no experience in the field. By some miracle, I got the job.

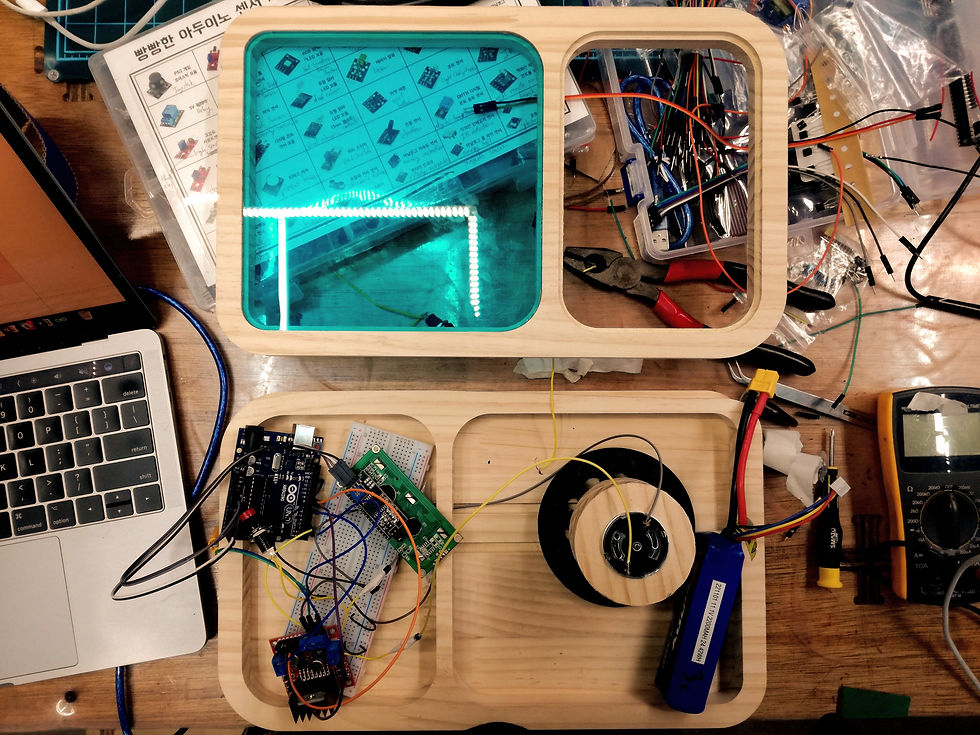

On our first day, my colleague and I were told that we had less than three months to build a centrifuge from scratch as well as make a functional product from bacteria. From scratch? Functional product? These terms scared me because I didn’t know the first thing about programming revolutions per minute on a DC motor, building an electric circuit, or designing something out of, well … germs.

Failure is an attitude

Little did I know that we were being thrust full-force into a process that would teach us the Maker Attitude. The Maker Attitude encompasses the belief that we are all creators. This necessitates that we embrace failure as an opportunity for growth, and view the iterative process of ideation and prototyping as stepping stones towards mastery. My friend's “Hot Nozzle” (the energy-efficient water heating system) didn’t garner much success at first. The idea came to him in 2014 when he was still a grade-10 boarding student and was fed up taking cold showers because the school’s geyser couldn’t retain its heat.

I spent my three months at Fab Lab Seoul pretty much failing all the way. I was stuck down a rabbit hole of Youtube videos, online forums and tutorials. What I learned from the experience is why failure is so important.

The failure I’m talking about is the outright, embarrassing, you-haven’t-got-a-hope kind of failure. Like tinkering with an LED for one week and watching six different YouTube videos, three of them administered in Urdu by teenage boys, before realizing your mistake was in a single line of code. Failure is watching your electrical component start to smoke and burn because you got your wiring wrong for the fifth time. It’s realizing that your “vegan leather” made from kombucha is too sticky to work with because you forgot to wash it with soap, again.

What amazed me was that each time another eight hours went by and I hadn’t managed to do the thing I had set out to do, my mentor’s immediate response was, “That’s fantastic, and good luck with failing some more!” I often felt frustrated that I wasn’t getting enough guidance on the project, but the truth is, it was more a frustration with myself for not doing things right. It made me recognize how easily I give up and just how averse I’ve become to doing things that are difficult. We do what is safe because we know it guarantees an easy path to success. But is it the success we really desire?

To fail is to live fully

There are some moments when we know that doing what scares us is exactly what we need to do. Sometimes, the uphill grind, the constant failure and the discomfort are what really satisfy our drive. And through that process, we gain a lot more than the simple outcome of the task. We learn what it means to live. Living involves failing – again and again, and again – and then realizing that regardless of the outcome, the value is in the doing.

My friend is taking on the risk of failure by quitting university to pursue his entrepreneurial passions full time. I took on the risk of failure when I gave up a full scholarship to attend a weird university that no one had heard about and where you never even meet your lecturers face to face.

Where does your next potential failure lie? Probably in the direction you ought to be moving, for a life that is truly meaningful.